Corporate users in marketing and sales departments frequently need to produce complex documents. Proposals and RFQ/RFPs fit into this category. Modular documents make it easier to produce these files, but Microsoft Word is is not modular by nature.

Users need to add and remove sections of the document to increase the relevance to the potential buyer. If you’ve used Microsoft Word for more than a few minutes, you’ve noticed that its documents are not modular in the least. Each section in a document is dependent on information from other sections. Even the trained Word users find it difficult to remove a Word section or set of pages without trashing the whole file.

The wrong path: Trying to use PowerPoint for Modular Documents

For some clients, this leads them down the wrong road. They notice that PowerPoint has great page modularity. You can remove slides, move them around and add new ones without having any effect on the existing ones. So they request that their proposal template be formatted in PowerPoint. Genius brainwave? NOT!

PowerPoint is missing so many long-document functions that this is a terrible solution. What you gain in modularity, you more than lose in productivity. PowerPoint is missing typestyles, automatic tables of contents, page margins, end notes, table styles, cross-referencing, bookmarks and much more. Users can get around all of these by spending more time manually formatting, but isn’t that what the client was trying to avoid in the first place?

There are 2 alternatives for modular documents. Both are better than the PowerPoint “solution”. One is Microsoft Publisher, and the other is good old Word, used in a slightly different way.

Microsoft Publisher for Modular Documents

First, I’ll cover Publisher, because it’s less well known and deserves to be used more. Microsoft Publisher is included with many versions of Office, so it’s likely your client already has it installed. It follows many Microsoft conventions, so the learning curve is not too steep. Publisher is a full-fledged desktop publisher program with an interface similar to Adobe PageMaker, if you’ve been around that long.

Unlike Word, Publisher uses CMYK and Pantone colors, does color separations, has measurements to 1/1000″ and, most germane to our discussion, has Master Pages! This latter feature makes it easy to create a modular document. All pages are completely independent of one another. No section or page breaks to foul up formatting. No pictures anchored to text that move around. The main catch with Publisher is that people don’t know it’s there, so they have to do some learning.

2024 Update: Microsoft has announced that they’re retiring Microsoft Publisher. After October 2026, Publisher will no longer be included with Microsoft 365. This is unfortunate, as Publisher can do things that Word cannot.

There is another way that’s still better than PowerPoint for proposals. Word!

Using Word for Modular Documents

Word is useable for modular documents as long as you know about Master Documents. A Master Document is like a super file that links a number of Word documents. Simply put, you create separate Word files for each section of your long document. Then you use a Master Document to link them for printing. The sub-documents can be edited, moved and deleted with ease. Your client gets flexibility in document structure and only has to learn one new thing!

Word has had this feature for a long time, but it got a bad reputation. This was because users would assemble Master Documents and then try to maintain the large assembly as one entity. Almost inevitably, corruption of the Master Document would ensue and users would have to start over. So what’s changed?

Over the years, Word has gotten more stable. The Master Document feature doesn’t get corrupted as easily. But the deepest secret is that you create a Master Document to print the files, then you throw it away! Trying to preserve it by editing it is what creates the problems, so don’t try to preserve it. A Master Document is a temporary device used only at output time. Remember that and you will never have a problem.

We can help your client with Master Documents. We write tutorials that cover every step of creation, assembly, printing and follow-up. We also write macros that create instant Master Documents from a folder full of sequenced Word files. This is much easier than toiling away with manual formatting in PowerPoint. Give us a call to solve your modular document challenges, or email me at production@brandwares.com.

As I write this, our clients have a mix of Office versions deployed. Some corporations are still using Office 2003, while many others have taken the Office 2007-2010 plunge and been “Ribbonized”. The most difficult are the companies that have a mix of both. This platform mix is most challenging when PowerPoint is the target program. This is because of the different way masters and layouts are used.

PowerPoint has 2 layout mechanisms: the master and the layout. Masters are customizable pages that contain graphics and text that are in common to all slides. Layouts are arrangements of text and graphic placeholders that are superimposed on the master to make the final slides. PowerPoint 2003 opened up new possibilities for presentation design by adding multiple masters. Instead of just 1 master each for slides and titles, you could now create different masters for different purposes. This made it much easier to create a presentation with varying sections and special-purpose slide designs.

Masters and Layouts in PowerPoint 2003

In PowerPoint 2003, you access the masters using the View>Master>Slide Master command. Masters display in a sidebar, where you can create rename, duplicate and create masters. You can create a slide master or a slide/title master pair, but a title master cannot exist on its own. The primary difference between a slide and a title master is that the slide master has a multi-level text placeholder, while a title master has a subtitle placeholder with only one level of text.

There are 2 problems in PowerPoint 2003, though. First, Microsoft’s user interface design for accessing these masters is counter-intuitive and hard to use. And second, slide layouts are still closed to customization. This lack of customization means that multiple master slides are often necessary to create all the slide designs that may be needed.

Masters and Layouts in PowerPoint 2007/2010/2013/2016

When Office 2007 came out, the program that was most improved was PowerPoint. In addition to long-missed features like tracking/kerning and a more discoverable user interface, Microsoft had finally made slide layouts customizable.

To access masters and layouts in PowerPoint 2007-2010, click on the View tab of the Ribbon. Then click on Slide Master in the Presentation Views group. The master is the larger thumbnail at the top. The layouts are the 11 automatically generated slides below it. Not all of these are useful. The layouts you will probably reuse are the Title Slide, Title and Content and Section Header layouts, immediately under the master. The Title Only and Blank layouts at positions 6 and 7 are also widely used.

The shift in emphasis from masters in PPT03 to layouts in PPT07 means that creating a presentation template for PowerPoint 2003 is very different from later versions. In PPT03, all customization has to be packed into the masters. In PPT07, masters become much less relevant, with most customizations built into the layouts. Multiple master slides are only necessary to use a different Color Theme, since each Master and its Layouts can only use one color theme at a time. This is a change from 2003, where each slide could have a different Color Scheme applied.

As far as support goes, a PowerPoint 2003 presentation with multiple masters will almost always require an extra tutorial. This must explain masters, layouts and their application, because Microsoft’s interface is so bad. PowerPoint 2007 usually needs only a sample presentation that shows how the different layouts are used.

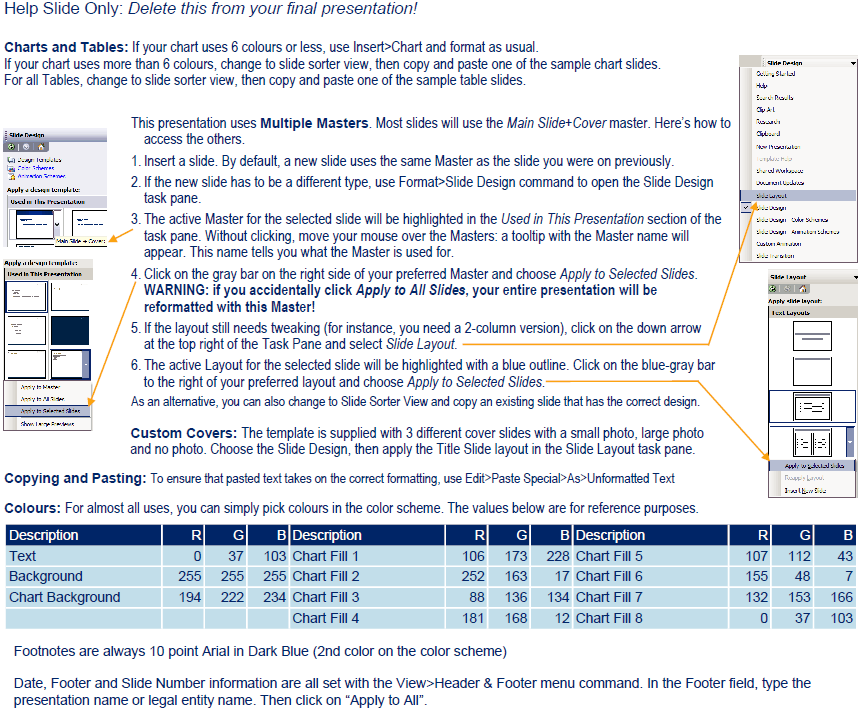

Content from a typical tutorial slide. Multiple Master presentations in PowerPoint 2003 need this information to make them useable.

The scenario that will having you tearing out your hair is the “blended family of Office versions” client who has both Office 2003 and 2007 users. These clients often believe Microsoft’s hype about 100% cross-compatibility between Office versions. PowerPoint is not totally compatible. Masters, slide layouts, charting and color palettes are all different. Behind the scenes, Microsoft has implemented eye-rolling kludges to simulate compatibility. Let me repeat: PowerPoint is not totally compatible!

In fact, the only program where we will not upgrade an older 2003 file to a newer version is PowerPoint. Instead, we rebuild it. If you’re creating a presentation that uses palette-switching to create sections with different color schemes, there is no other possible workflow. It’s the only way to guarantee it’s going to work correctly for the long term.

The best scenario is when the client is using PowerPoint 2007 or better. Compared to earlier versions, the new PowerPoint is a delight to work with and finally offers the capabilities that designers have been assuming were there all along.

Love it or hate it, but Microsoft has made decisions on how you should work with office software. Working within their limitations, your users can have productive careers and get things done. Ignore the limits and you are sentencing your users to hours of formatting hell. A prime example is Office charts

Office charts should have 6 colors maximum. The is a rule made by Microsoft. The exception to this rule is charts in Excel 2003 and earlier, which can have a maximum of 56 colors (see my previous posts for the details on Excel 2003). The following applies to Microsoft Word, but it’s more often a problem in PowerPoint.

If you design charts with more than 6 colors, you are forcing your users to either:

- copy, paste and reformat a sample chart into the one they want, or

- manually enter the colors for the series above 6 from a reference table of RGB values.

Neither of these could be considered a PowerPoint “Standard Operating Procedures”. Both workarounds are slow and error-prone.

Office Charts in Office 2003 for Windows or 2004 for Mac

PowerPoint 2003 Some color palette slots are used for as many as 3 functions. This makes it tricky to design a color sequence that works for all purposes.

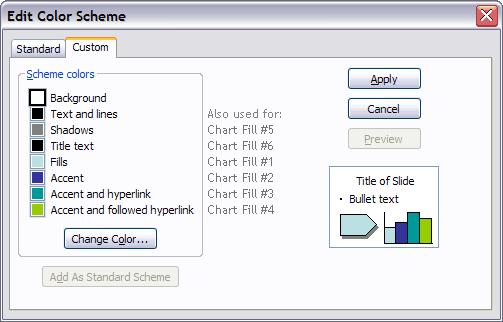

PowerPoint only has code in place to automatically assign 6 palette colors to charts. In PowerPoint 2007 and higher, these are 6 distinct colors that are only used for charts and object fills. In PowerPoint 2003 and earlier, the chart colors are taken from the 8-color palette that is used for other elements as well. This has consequences you have not considered. Here’s how it works:

PowerPoint 2003 and earlier have color palettes with 8 colors maximum. In order, the colors are used for Backgrounds, Text and lines, Shadows, Title text, Fills, Accent, Accent and Hyperlink and finally Accent and followed hyperlink. Applying the recommended color position to a presentation element will mean that that element can be automatically updated if the palette is changed. This is a handy way to create color-coded sections in a presentation.

However, the same colors are used for Office charts. The colors are assigned in this order: Chart Color #1 is always taken from the Fill position. CC#2 is Accent, CC#3 is Accent and hyperlink, CC#4 is Accent and followed hyperlink, CC#5 is Shadows and CC#6 is Title text. Therefore, if you have designed a series of chart colors that is different from the code colors used the the presentation, you must give your users one of two headaches:

User headache number 1: You assign the color palette positions to create an automatically-filled chart, then manually assign all other presentation elements with RGB colors. This means new charts look swell, but color-coded sections cannot be easily updated. In fact, the colors of the entire presentation are must be updated manually element by element. Slow!

User headache number 2: You assign the color palette positions to the correct elements i.e., Title text is filled from the Title text palette position. New charts come in with goofy colors and each series must be manually reassigned from RGB values.

For PowerPoint 2003 and earlier, Microsoft has decided you only need 8 colors for everything. Designing with more colors does not make it a better design. It just makes it harder to use.

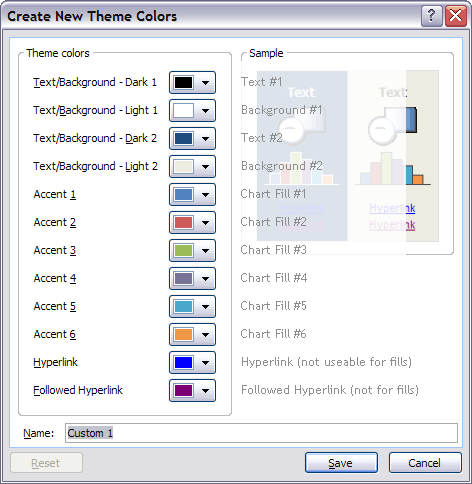

Office Charts in Office 2007/2010/2013/2016 for Windows or 2008/2011/2016 for Mac

For PowerPoint 2007 and later, Microsoft has decided you only need 12 colors for the presentation. Fortunately, now there is separation between color functions, with 2 colors for backgrounds, 2 for text, 6 for charts and fills and 2 specifically for hyperlinks. But you still only get 6 automatic chart colors. And in Office charts as in so many Office features, if it isn’t automatic, it’s a time-waster. So the advice still holds that speccing more colors is really imposing lower productivity on your users.

Charts apply this sequence in a predictable way. In a standard column chart, the leftmost column is color #1, with each extra column getting the next color in the sequence. Stacked columns display color #1 as the bottom layer and pie charts apply color #1 to the first pie segment, and by default this pie segment has its left border at 0 degrees, pointing straight up. If you design the presentation with this in mind, implementation is easy for the user.

In Office 2007 and later, there is one potential workaround that gives users access to 10 additional colors. It’s the Custom Color XML hack. This hack adds colors to the color picker in Windows and in Office 2016 for Mac. These colors cannot fill charts automatically and they will not show in the Office 2008 or 2011 for Mac color picker. However, it’s still a less cumbersome workaround than the 2 kludges I mentioned at the start of this article.

Are these limitation fair? No. Are Microsoft’s choices well considered? Not really. Are you going to change the way PowerPoint works by ignoring its limitations? Sadly, the answer is also no.

My recommendation is to incorporate a little Zen into your attitude, accept that PowerPoint (particularly the 2003 and earlier versions) is a deeply flawed and limited program. Then go and create some great Office chart designs with 6 colors or less that are easy to use.

Users create charts in Excel and import them to Word and PowerPoint. Reports frequently require charts. Put these together and you’ll see that when a client asks for a report template, you should also be giving them a compatible Excel template for the report charts they will need.

These charting templates do not have to be complex. Defining a default font and color palette is usually sufficient. The actual steps differ between Excel 2003 and Excel 2007/2010/2013/2016, so make sure you ask your client what version they are using.

The first step with any program is to design the color palette. Excel uses the colors in the order they are entered. In a bar chart, the colors are used left to right as each data series is added. Pie and doughnut charts always start with left edge of the first segment at the 12 o’clock position and proceed clockwise from there. Go with the flow and enter palette colors in the order you want them to appear by default. There is only 1 palette sequence active, so all report charts in your design should use the same color order, or you’ll drive your users crazy.

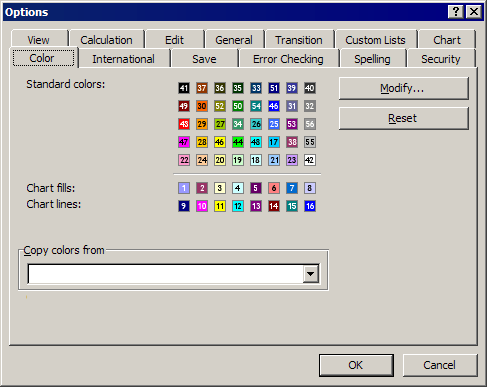

Report Charts in Excel 2003

The numbers show the order used in Excel 2003 charts.

If your client is using Excel 2003 or earlier, open a spreadsheet in that version, use the Tools>Options command and choose the Color tab. For each color in the “Chart fills” row, start at the left, click on a color, then click on the Modify button. Choose the Custom tab and enter the RGB values. Click on OK, then choose the next Color fill patch to the right and repeat.

Occasionally Office 2003 clients will insist on more than 6 chart colors. In that case, keep filling palette spaces with custom colors using the order shown in the illustration. This will give you up to 56 custom data series that will automatically be filled correctly. Be forewarned, when your client upgrades to a later version of Office, they will, in effect, be back to 6 chart colors. Later versions of Excel do not allow this extended palette.

As a final step, choose Format>Style, ensure the Normal style is selected and click on the Modify button. On the Font tab, set the font to the desired typeface, size and weight to match the Word templates into which these will be inserted. OK out and save the file as a template with an “.xlt” file ending. You’re done!

Report Charts in Excel 2007/2010/2013/2016

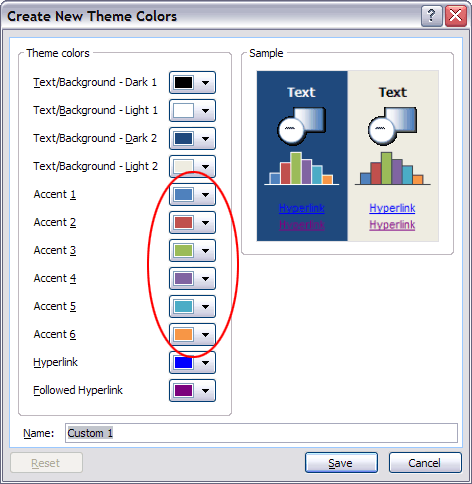

Circled: the 6 colors that will automatically color Excel 2007-2016 charts.

For clients on Excel 2007 or later, the palette system works differently, and not for the better. Users have lost the capability to set 56 chart colors, now you can only preset 6! The Office 2007/10/13/16 Theme Color dialog displays slots for 6 Accent Colors. Set these with RGB values in the sequence they are t appear in the report charts. If report charts use more than 6 colors, Excel’s default behavior is to color the additional series with automatically generated tints of these 6. To get more custom colors, users must enter them manually. In real life, they’re probably not going to do this. First they have to turn off the automatic series fill, then they have to look up the colors they are supposed to use (where is that tutorial again?), then they have to enter the RGB values. It’s just not a realistic workflow for end users on a deadline.

One alternative is to create a sample chart with manually filled extra data series. This looks good for a client sign-off, but in actual production, the user has to find the sample chart, copy and paste it to their presentation and then change the chart type and data to match what they are trying to show. Again, most users are unlikely to go to this trouble, especially if time is tight.

Finally, if you’re up to a little XML hacking, you can add up to 10 custom colors to the Windows color picker by using my tutorial XML Hacking: Custom Colors. While these colors are not used automatically in chart fills, it’s a simpler process to fill a series by clicking on a custom color than looking up an RGB value.

If possible, it may be best to try talking your client out of using more than 6 colors for charts. The lower expectations will make everyone happier and the end-users would thank you, if they knew who you were.

To wrap up this template, click on the Page Layout tab of the Ribbon, look for the Themes group and click on the down-pointing arrowhead beside Fonts. Click on Create new theme fonts… at the bottom of the list. Set the fonts for both Heading and Body and click on OK. Save the file as an Excel Template with an “.xltx” ending and distribute with the report templates.

An alternative workflow is to save the themes from the Word or PowerPoint file that accompanies the Excel template, then apply those themes to the Excel worksheet. Or course, you still have to apply the same thought process in arranging the colors to create charts that automatically have the right color sequence. It helps that charts created directly in Word or PowerPoint follow the same logic and color order.

Report Charts in Excel 2008, 2011 or 2016 for Mac

In Mac versions of Office, you’ll have to create the Color Theme in PowerPoint, then import it to Excel. Unfortunately, while you can use the Custom Color XML hack to add custom colors to a color theme, you can’t preview them in Office 2008 or 2011.

For the font theme, you can use my tutorial XML Hacking: Font Themes and apply the resulting theme to your Excel template.

The Invisible Characters are Word formatting entities, hidden by default. Master them to rule Word. Ignore them and you are just another Word user stumbling in the darkness.

Last week’s post covered how to display these invisible characters. If you’re not sure what the heck we’re talking about here, go back and read that post first.

Page and Column Break Invisible Characters

Chief among the invisible characters are the Breaks. Microsoft used to group all the breaks together in Word for Windows and still does on the Mac, even though their actual functions are very different. Let’s begin with the “safe” breaks, the ones that won’t wreck your document. These are the Page and Column Breaks, invisible characters #1 and 2.

The Page Break creates a new page immediately after it.

A Page Break is a special character that tells Word to start a new page. That’s all it does, it’s very straight-forward to use. Entering or deleting a Page Break will never screw up your document. This is the best way to create a new page.

Do not ever create a new page by typing a series of carriage returns. NEVER! EVER! The space taken by a series of carriage returns is a function of the specific font installed on your computer. Change fonts or move the file to a new computer and the carriage return space can easily change. The result is that your next page copy creeps on to the preceding page, or the new page starts with a blank line at the top. Not good. Just insert a Page Break and be done with it.

The Column Break starts a new column. In the last column on a page, it starts a new page.

Invisible character #2 is the Column Break. This is similar to the Page Break, but it creates a break to the next column and when you’re in the last column, a break to the next page. Inserting a Column Break in a 1-column layout has the same effect as inserting a Page Break.

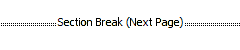

Section Break Invisible Characters

Then we get into the Section Breaks. These are a different animal than the Page and Column Breaks and can wreck your formatting if not used with care. Section Breaks hold information for the preceding section such as margins, page layout and header & footer formatting. Deleting a Section Break forces the section that it ended to take on the formatting of the section after it. The Section Break at the end of the amalgamated sections is now in charge.

The Continuous Section Break creates a new section without creating a new page.

The most useful of the Section Breaks is the Continuous Section Break (invisible character #3). This creates a new section without creating a new page. A Continuous Break will automatically balance columns in the section it ends. It’s indispensable in fillable forms, since it marks the boundary between free-text and locked areas of the form. When you need to create an area with a different number of columns, reach for the Continuous Break.

This creates both a new section and new page immediately after it.

Invisible #4 is the Next Page Section Break. It’s also the most dangerous, because some users assume it’s equivalent to a simple Page Break. They insert them everywhere they want a new page and end up with dozens or hundreds of sections in their document. Then they wonder why their footers are messed up! Next Page Section Breaks should not be common. Use them to insert a landscape page in the middle of a portrait document, to create new chapters or other regular distinctive section formatting, or to format a different last page. Other than that, you probably shouldn’t be using them.

The Even and Odd Page Section Breaks create a new page and section with the corresponding header or footer type.

Then we have the Even and Odd Page Section Breaks (invisible characters #5 and 6). Once every 10 years you need these. They are used in conjunction with even and odd page headers/footers and don’t do much else. Their only function is to force an even or odd page header or footer where one would not naturally occur.

Paragraph and Anchor Invisible Characters

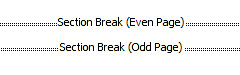

Now we move on to other invisible characters that have a more local scope: they only affect a small area of your documents. The most important of these is Invisible #7, the Paragraph Mark. Its function is analogous to the section breaks: the Paragraph Mark contains the formatting for the preceding paragraph. Delete it and the Paragraph Mark from the following paragraph takes over.

The Paragraph Mark holds the paragraph formatting for the paragraph it ends.

Paragraph Marks contain the default character formatting for the paragraph, plus all paragraph formatting such as indentation, line spacing, tabs, bullets and numbering

Paragraph Marks also serve as the character to which graphics, frames and text boxes are anchored. That brings us to invisible character #8, the Anchor. In Word, every item is either in the text string, or is anchored to the text string. The default anchoring is for the graphic to be positioned relative to the paragraph to which it is anchored. This makes for a very fluid document: when text is edited, the anchored pictures move around to stay close to their Anchors.

The Anchor shows to which paragraph mark a graphic or text box is anchored.

You can change the positioning to be absolute, so the graphic stays in the same position regardless of where the anchor is on the page. This does not eliminate the anchor! If the text moves to another page, the anchored graphic moves with it. It is not possible in Word to place a graphic on page 5 and have it stay there. It is always anchored to text and when the text moves, the graphic moves too.

By the same token, if the paragraph mark to which the graphic is anchored is deleted, the graphic will also be deleted!. This is why it’s so important to make those invisible characters visible. You really can’t see what you’re doing otherwise.

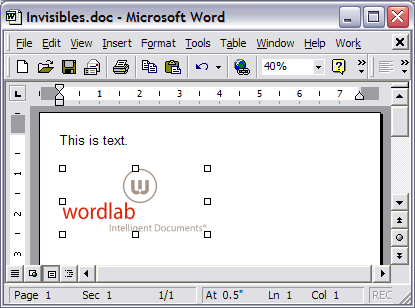

Bonus: the Bookmark Invisible Character

The square grey brackets show bookmarked text. Each Bookmark is named, to facilitate referencing it.

Today’s bonus invisible character is the Bookmark. Technically, this isn’t a character, it’s a range (an arbitrary subsection of a document similar to a selection). Bookmarks enable you to automatically relay information from one part of a document to another. One example is a document title that you also want to appear in the footer of each subsequent page. Select the title, insert a bookmark. Then, in the footer, insert a REF field. This field links back to the bookmark and always keeps the footer correctly updated. An easy fix that looks like magic to your clients. But you have to be able to see the bookmark!

Word’s default settings hide crucial formatting information. Professional editing of Word docs requires you to change the program’s display parameters.

In effect, paragraph formatting is stored in the paragraph mark and section formatting is stored in the section break after the relevant content. But Microsoft decided users wanted a pretty interface rather than a functional one, so they chose to hide both entities by default. Every hour of every day, thousands of documents are getting mangled because of this design decision.

Likewise, every graphic in a Word document is anchored to a paragraph. Delete the paragraph, poof, graphic gone. Move the text to a new page and the graphic moves with it. But the anchor is invisible! Let’s fix this!

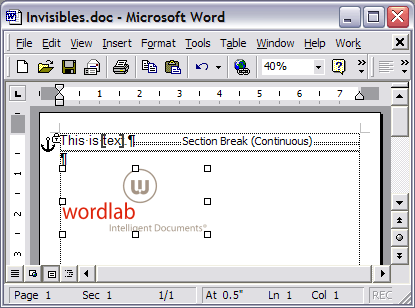

The normal Word view: pretty, but not informative.

Here we can see that the graphic is anchored to the first paragraph and that anchor is locked. The first paragraph is separated from the second by a continuous section break, which means the page formatting could be totally different for the two paragraphs. The word “text” has been bookmarked. We can take care to format this without ruining any of these characters, now that we can see them.

Word’s Useful View

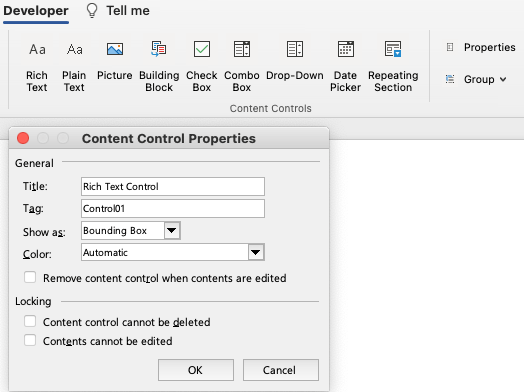

How to Set Up Word for Windows for Professional Editing

The first step to professional editing in Word is to display all the hidden formatting marks. Here’s how to do that in each version:

Word 2003

- Choose Tools>Customize>Options.

- Uncheck Show full menus after a short delay and

- Check Always show full menus. Click on Close.

- Choose Tools>Options>View.

- In the Show section, check Bookmarks.

- In Formatting Marks, check All.

- Under Print and Web Layout options, check Object anchors, Text boundaries, White space between pages and Vertical ruler.

Word 2007

- Click on the Office button and then on the Word Options button.

- Select the Display pane.

- Check Show all formatting marks.

- By default,Show white space between pages in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

- Now choose the Advanced pane.

- Under the Show document content section, check Show bookmarks and Show text boundaries.

- By default, under Display, Show vertical ruler in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

Word 2010

- Click on the File tab and then the Options button.

- Select the Display pane.

- Check Show all formatting marks.

- By default,Show white space between pages in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

- Now choose the Advanced pane.

- Under the Show document content section, check Show bookmarks and Show text boundaries.

- By default, under Display, Show vertical ruler in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

Word 2013 and 2016

- Click on the FILE tab and then the Options button.

- Choose the Display pane.

- Check Show all formatting marks.

- By default,Show white space between pages in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

- Now select the Advanced pane.

- Under the Show document content section, check Show bookmarks.

- By default, under Display, Show vertical ruler in Print Layout view should already be checked. If not, check it.

How to Set Up Word for Mac for Professional Editing

Word 2004, Word 2008 and Word 2011

- Choose Word>Preferences>View.

- Under Show, check Object anchors, Bookmarks and Text boundaries.

- Under Nonprinting characters, check All.

- Under Window, Vertical ruler should already be checked. If not, check it.

Word 2016

- Choose Word>Preferences>View.

- Under Show in Document, check Object anchors and Bookmarks.

- Under Show Non-Printing Characters, check All.

- Under Show Window Elements, Vertical ruler and White space between pages in Print Layout View should already be checked. If not, check them.

Some Useless Options

Unchecking these options can save your time and sanity:

- When selecting, automatically select entire word, to enable per-character formatting and correcting,

- Keep track of formatting, so Word will not create a new style for every little formatting change, and

- Scale content for A4 or 8.5×11″ paper sizes, so all branding and placed graphics will print undistorted.

Just doing these steps will give you a leg up on 99% of the rest of the world in terms of professional formatting in Word. The great majority of formatting screwups are the result of inadvertently deleting the hidden formatting characters. Next post, we’ll get into more details about how these formatting marks actually work.

2024 Update: Microsoft has announced that they’re retiring Microsoft Publisher. After October 2026, Publisher will no longer be included with Microsoft 365. This is unfortunate, as Publisher can do things that Word cannot.

Is Microsoft Publisher better than Word? For design-intensive documents like newsletters, the answer is YES!

We recently had a request to transcribe a full-scale 16-page magazine layout from InDesign to Word. We recommended using Microsoft Publisher. In addition to the usual Word, PowerPoint and Excel, many versions of Office include Microsoft Publisher, a lightweight but capable desktop publishing program.

MS Publisher is comparable to PageMaker, for those of you that have been in the industry long enough. The interface is similar enough to other Office products that the learning curve is fairly low. But the best part is that it’s free and already installed in most offices. Your client doesn’t have to buy or install anything to get good quality design documents.

Users will find useful features like:

- master pages,

- Pantone and CMYK color models,

- the ability to make color seps and print to a real press,

- measurements to 1/1000 of an inch and

- many others.

Word doesn’t have any of these.

Microsoft Publisher for Modular Design

But perhaps the greatest advantage lies in a fundamental design choice in Word. Publisher does not link everything to the text stream. Just like InDesign and Quark, pages and graphics exist as independent entities that stay where you put them. In Word, all page breaks, placed graphics, column breaks, etc. are anchored to the text string. When the text is edited, all elements move in relation to it. This isn’t a defect, just the fundamental difference between a word processor and a page layout program.

Designers rarely recommend Publisher simply because they’re unfamiliar with it. It’s a Windows-only product, so they don’t see it in their copy of Mac Office. Microsoft doesn’t advertise it as a feature product. But Publisher is ideal for newsletters, brochures and magazines. Consider it for any document where you need a flexible layout with lots of graphics, photos and articles.

These types of files can be done in Word, but they are always less reliable and more limited. Word is still a better choice for documents that must be editable by anyone at the client’s office. Publisher is not universally installed and does require a little familiarity. For design-intensive Word files, we suggest additional tech support time to help handle the inevitable “I deleted a paragraph and my photo disappeared as well!” questions.

Microsoft Publisher Case Study

New York University needed a flexible ask brochure to help raise construction funds from donors. They required an electronic document that could have pages added and removed at will (not a strong point of Word!). They also needed to customize the brochure with each donor’s name and information before printing it out on a color copier. Publisher met their needs for handling large linked graphics and color consistency using Pantone specs. Here’s what the cover looked like:

Cover of NYU ask brochure in Microsoft Publisher

Do you have a client newsletter project coming up? Give us a call at +1 201 664 6007 to discuss whether Microsoft Publisher might suit your client better.

Theoretically, there is no such thing as RGB tints. Color theory uses “tint” as any lighter hue of a color. Often this will be explained as what happens if you mix a color with white, though anyone who has spent any time mixing colors has noticed that adding white pigment changes colors in other ways than simply making them lighter.

In the commercial art world, tint is nearly synonymous with screen, because the traditional way of creating lighter shades of a base color is to print it with a halftone screen.

Because of this tradition, brand guidelines often augment a base set of colors with a subset of pastels referred to as tints or screens. This all makes perfect sense in a print-oriented world. However, when you move into digital display color, there are no screens any more. So how do we interpret brand guidelines for RGB-only software like Word, PowerPoint, Excel and the web?

Brand guidelines now normally include RGB numbers for the base colors of a brand, but tints rarely have an RGB equivalent. The designer just specs 20% of PMS 286 and lets you figure it out.

A Calculator for RGB Tints

You can do it with Illustrator, but it’s a little roundabout. You create an RGB color, save it as a swatch, being sure to over-ride Illustrator’s efforts to keep turning it into CMYK. Then you can spec a percentage of the swatch and finally find out the RGB value of that percentage.

Or you can just use the handy dandy RGB Tint calculator on this very web site. Simply enter an RGB or hexadecimal color value, then the tint percentage, and you get an instant readout of the new color values along with a preview of the color appearance. In addition, it makes a useful RGB-hexadecimal convertor, though there are plenty of other ways to do that operation.

This is a tool we developed for our own template creation work, but you may as well get some use of it too. Enjoy!

In my last post, I covered some basics on logo production for use in Word, PowerPoint and Excel. This post will continue that topic with some trade secrets, tips and tricks to make logo production easier.

Let’s start at the beginning with the file that’s to be turned into a graphic. Is there a black element in the logo? If there is, you need to do some special handling. In most design programs, black is not necessarily black. Most artists, coming from a print production background, assume that applying C0 M0 Y0 K100 will give them black. If this was a logo you were actually printing, it would. But you’re not.

You’re going to translate this logo into RGB, which is the only color model used by Word, PowerPoint and Excel. (If you use Office on the Mac, the color picker makes it appear you are choosing other color models, but behind the scenes your choices are all translated to RGB.)

If you watch the color values in Illustrator, when you change C0 M0 Y0 K100 to RGB, you’ll see that you do not get black (R0 G0 B0). You get dark grey, something like R35 G31 B32. Shake off that print mentality! The rule of thumb is: on all designs destined for Office, change all color values to RGB, preferably using the Pantone Color Bridge values.

Logo Production Trade Secret

The trade secret for this piece is a shortcut that will save you lots of time at the cost of some system setup. For most logos, we do not use the Illustrator file that is linked to the final art. Instead, we use a PDF of the final art, since the logo has been placed at its final size here. To get our logo file, we resize the PDF to get the total number of pixels we want, make a screen grab of the logo, then paste it into Photoshop.

Here’s the theory behind what we’re doing. The screen grab is at screen resolution, but our final file must be print resolution at 600 d.p.i. (For PowerPoint, we use 384 d.p.i., which is exactly 4 times the default Windows screen resolution. This displays beautifully and still prints well.) So we’re enlarging the PDF to get the number of pixels we need on the display. Then when the screen grab is pasted into Photoshop, we tell it that the resolution is 600 d.p.i. If our math is right, the final logo will be exactly the same physical size as the final design, but at a high resolution.

Here’s the system setup part. The calculations are a LOT easier if both your screen and Acrobat are set to 100d.p.i. If you’re using Windows, setting your screen to 100 d.p.i. means opening your Display control panel, clicking on the Setting tab and the Advanced button. On the General tab, change DPI setting to Custom setting and try 104%. On most systems, that will get you 100 d.p.i.

Non-Retina Macs should already be running at 100 d.p.i. Now open Acrobat and choose Edit>Preferences>Page Display. Under Resolution, choose Use system setting, which should say 100 pixels/inch. OK out.

You should be good to go. Open the design PDF with logo, set the zoom to 600% and choose the Edit>Take a Snapshot command. Draw a marquee around the logo. Here’s a cool tip: even if the logo does not fit on your monitor, drag the marquee over to the side of the window, forcing the graphic to scroll. Acrobat captures all parts of the selection even after it has scrolled off to the side! When you let go of the mouse, the screen will blink, indicating that the image is on the clipboard.

Now switch to PhotoShop. Choose File>New and the suggested size should match the area you just grabbed. Change the resolution to 600 d.p.i. Paste the logo.

Now crop it. Our practice is to do the initial crop leaving one pixel of background clear on the top and left sides of the image. This compensates for Word 2003’s propensity to display the logo on-screen looking like the top or left is “clipped”, even though it prints fine. Crop the right and bottom edge to contain the faintest shading of the logo and no more.

Left: raw screen grab

Right: initial crop – 1 pixel top and left, no clearance right and bottom.

Minimal File Size with Precise Sizing in Office

Word, PowerPoint and Excel can only measure to 1/100″. So if your logo is big or small by a few thousandths, Word will resize it vertically or horizontally to make it fit. Your logo will be slightly distorted. So now we’re going to add back some of the background. In PhotoShop, choose Image>Canvas Size and change the units of measurement to inches. Round the numbers up to the next highest 1/100 of an inch, so 1.999 becomes 2.0, 12.742 becomes 12.75, etc. Set the canvas addition to flow to the right and bottom, as in this screen shot:

Dimensions rounded up to next 1/100″, canvas set to increase right and bottom size.

Click on OK. In the Layers palette, choose Flatten Image. Now follow the steps from last week’s post: choose Image>Mode>Indexed Color, set Palette to Local (Adaptive), reduce the colors to 8 for each color in the original logo (so a 2-color logo will use 16 colors), set Forced and Dither to None, click on OK. Save as PNG for most uses.

There you have it, your first professional Office-ready logo file! It will look good and print sharp, it will be size-accurate and the file size is tiny. Congratulations!

March 2017 edit: This article is still relevant if you must use bitmap-format logos. Vector-based logos offer significant advantages, like not getting blurry when image compression is used on the file. Here’s the state of the art: Best Quality Logos for Office

JPEG logos are the automatic choice for most artists when a client needs a wordmark in Office. It’s the worst possible format.

JPEG seems to be the all-purpose file format where the designer realizes they need to place an image with a smaller file size than a full-scale EPS or TIFF. The JPEG format is fine for photos and photo-like graphics, such as graduated tone areas. But it has 2 things going against it for flat color line art: lossy compression and the RGB color space.

The Disadvantages of JPEG Logos

Lossy compression renders flat color as a pixelated and sharpened hodge-podge where every pixel can be a different variation on the original color. You’ve all seen this on blowups of low-quality JPEGs where weird textures are introduced to areas that were formerly smoothly shaded. Lossy compression does reduce the size of the file, but at a visual cost. When you’re dealing with flat color, this visual cost is all too noticeable.

The other down-side to JPEG is the RGB color space. While admirably suited to photos, it’s simply not needed for line art logos. The RGB color space means thousands of color definitions are stored in the file, even for a logo that started as 1 color when it was a happy piece of vector art. This bloats the file size

The net result is a fuzzy, textured logo that is just too big. Then the client wonders why their letterhead template is over a megabyte before they type one word. Instead, let’s go back to first principles and figure out how to do this right.

The Alternative to JPEG Logos

The average logo starts life as an Illustrator file colored with one or two colors. How can we keep it as close to that original as possible?

Let’s start by throwing out the RGB color space. We don’t need millions of colors, we only need a few. Let’s use Indexed Color instead. With indexed color, only a few color definitions need to be stored in the file, so the file size goes way down. It goes down so much, that we can now increase the resolution of the image to get better sharpness.

Let’s go through it step by step. If you’re using Adobe products, it takes 2 steps to get to indexed color. First you have to export the logo from Illustrator as RGB, but to a file format that is not lossy, like TIFF. Then you open the RGB file in PhotoShop and reduce the image to indexed color.

Open a test logo in Illustrator. Start with a one-color version to make life simple. Now use the File>Export command with the following settings:

Save as type: TIFF

(Click on Save)

Color Model: RGB

Resolution: Other 600dpi

Anti-aliasing: Art Optimized (Supersampling) – assuming logo text has been converted to curves.

Check LZW Compression and click on OK

Now open the TIFF in Photoshop. Choose Image>Mode>Indexed Color and the following settings:

Palette: Local (Adaptive)

Colors: 8

Forced: None

Dither: None and click on OK

The format to save in depends on which version of Office your client is using (you did ask, didn’t you?). GIF format stores more compactly in Office 2003 and earlier. PNG has a smaller file size in Office 2007 and above. The difference is not huge and PNG has the advantage of remembering its resolution, so you could safely just stick with it if you’re not sure. GIFs always import into Office under the assumption that they are 72 d.p.i., which means your logo have to be reduced to the correct size after placing in Word or PowerPoint.

The Proof That JPEG Logos Suck

Are you skeptical that it’s worth the trouble? Here’s an enlargment of a typical artist’s result at left versus a Brandwares logo on the right:

Enlargement of a typical artist-supplied 300dpi RGB JPEG.

OK, it’s obvious the indexed color image looks way better. But the other benefit is that it’s also much a much smaller file size. Typically, the crappy-looking JPEG will be 8 (yes, eight) times larger! I know, file size may not matter to you, but it does to your client. They have to pay for storage for thousands of documents based on your template. The rule of thumb is: if your letterhead is bigger than 100kb, you’re doing something wrong. Ours range between 40kb and 90kb.

Enlargement of a Brandwares 600dpi indexed color PNG.

It’s not a lot more work to give your client a superior product. Forget JPEG as a logo format, just use it for photos. Indexed color PNGs are the way to go for line art.

March 2017 edit: This article is still relevant if you must use bitmap-format logos. Vector-based logos offer significant advantages, like not getting blurry when image compression is used on the file. Here’s the state of the art: Best Quality Logos for Office