This article presents some new ways to use color themes. To find out more about how color themes work in PowerPoint and other Office programs, please read this companion article as well: Great Color Themes – Brandwares Best Practices.

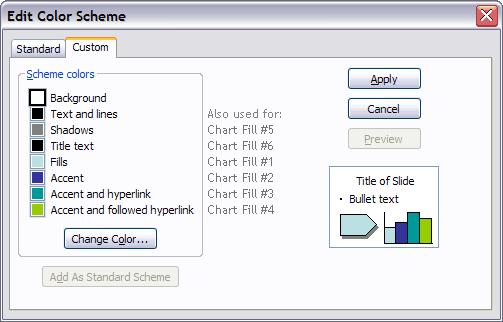

The simplest way to give a presentation variety through different topics is to apply new color themes. If you ever worked with pre-2007 versions of PowerPoint, you may remember that you could have unlimited numbers of Color Schemes (as they were called), that you could easily apply to groups of slides to give them visual cohesion with one another.

With the 2007 XML version of Office, that simplicity went away. Instead, a master slide could have only 1 Color Theme. Applying a Color Theme to a single slide now applies it to the master and every slide based on that master. For most presentations, it’s all or nothing with new colors. Fortunately, I figured out a workaround that brings back much of the color flexibility of earlier versions. Vari-colored sections are back!

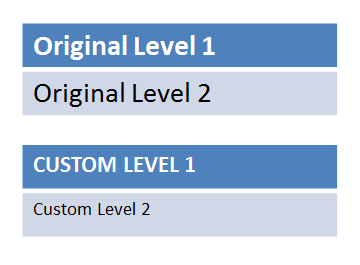

There’s still a limit of 1 theme per master, so now we have to create additional master for every different theme we want to use. Typically these themes will be closely related, with only 1 or 2 colors varying per theme. Sometimes the colors stay the same, but only change position in the theme. I’ll get into how you use that later.

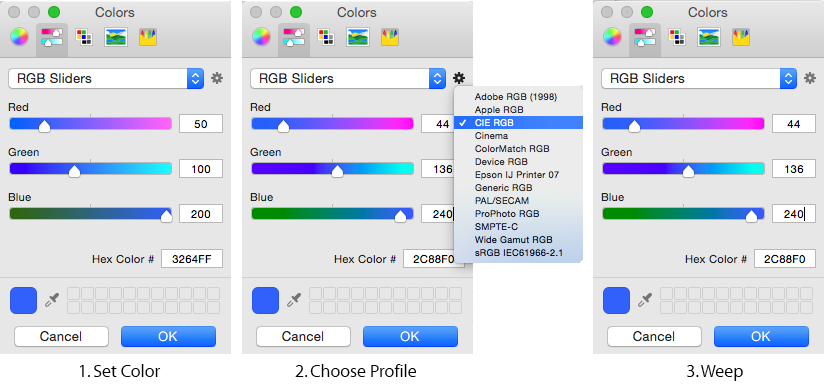

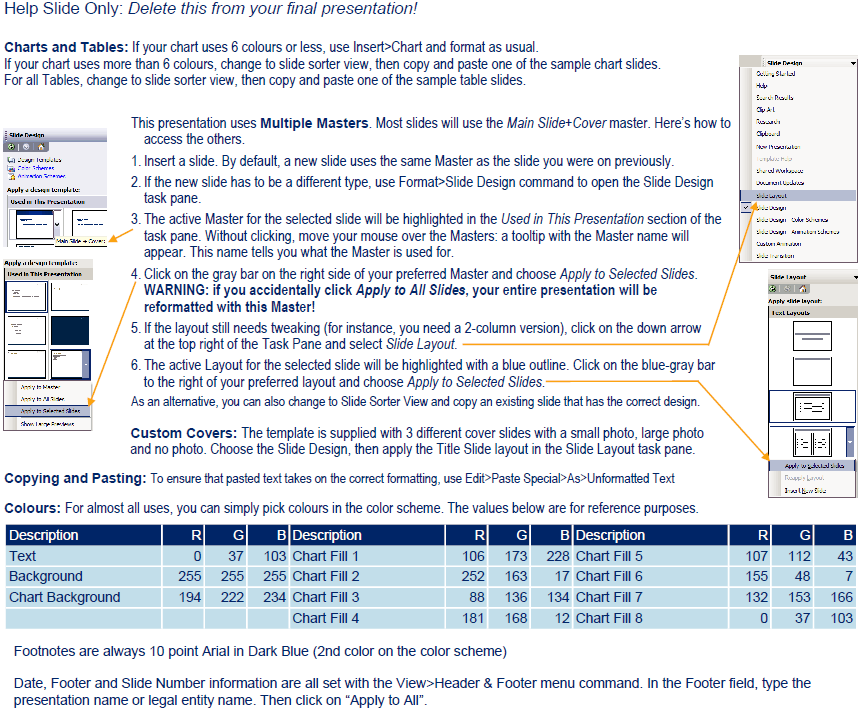

This screen shot shows the Master Slide (the larger one at top) followed by its Slide Layouts below. To add more Color Themes, we begin by copying the Master Slide. The copies of the Master don’t have to duplicate all the slide masters. If different colors are only needed for a chart, we’ll just attach one chart slide layout to the new master slide.

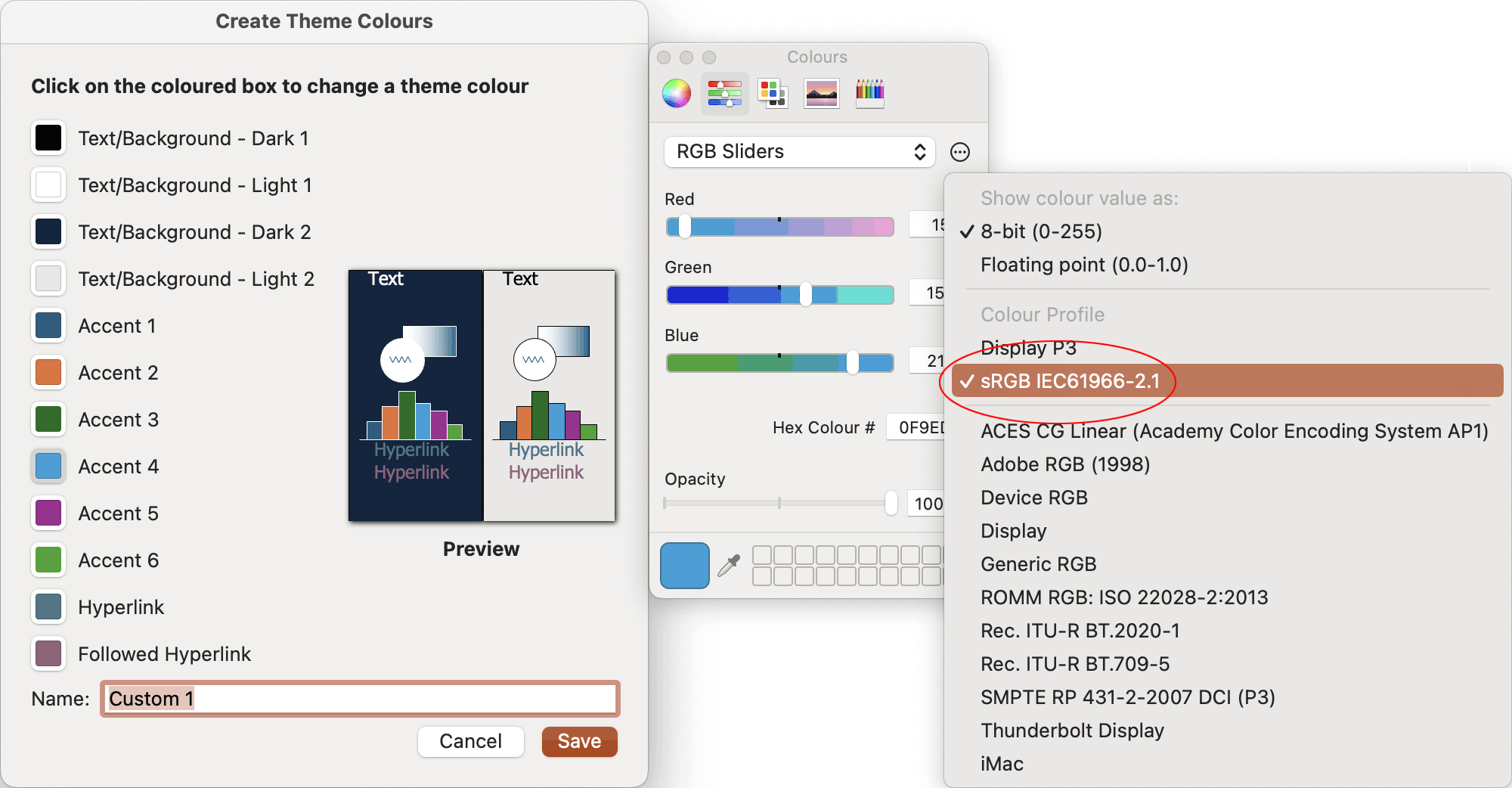

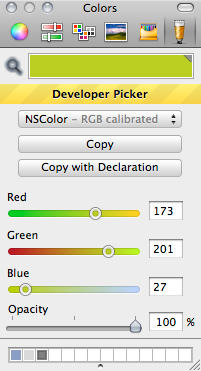

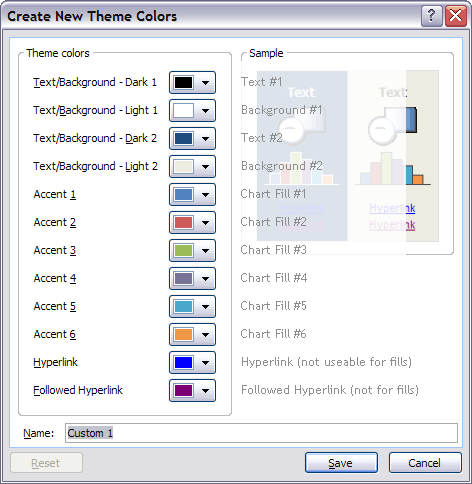

Then we create new color themes, attaching one to each master. After this, you could save the template and make a perfectly good presentation. To get the different color theme, you reapply layouts from different masters and the colors come along for the ride. However, it’s a non-intuitive way to apply colors. To create a better user interface, we need to hack some XML!

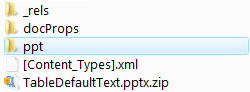

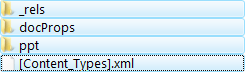

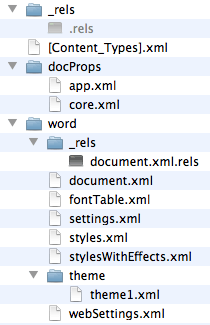

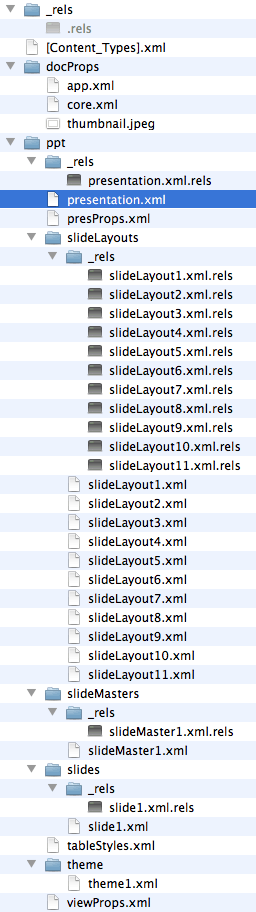

To begin, review the instructions in my previous post about opening Office files in a text editor. If you’re editing in OS X, there are operating system issues you need to watch out for. I cover them in XML Hacking: Editing in OS X. The files we’re going to modify are in the ppt>theme folder. When open it, you see 4 files:

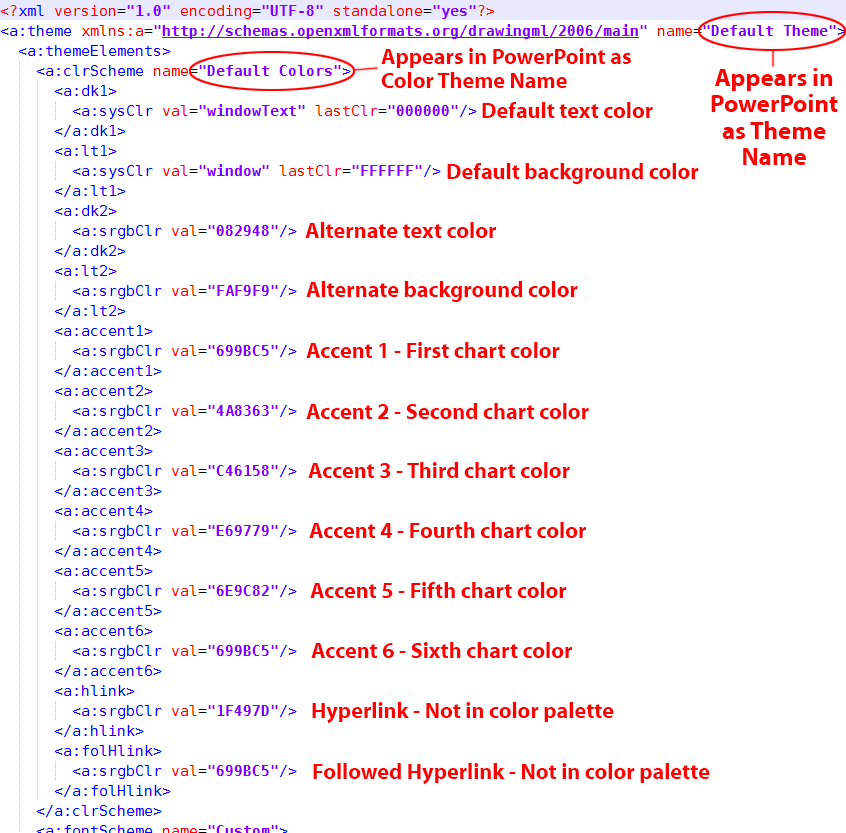

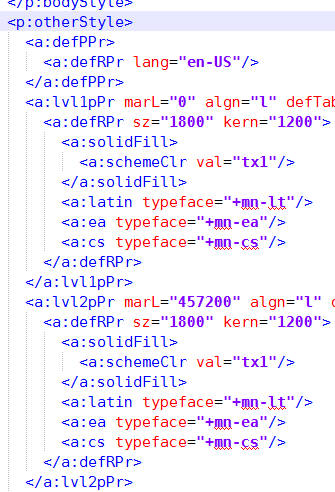

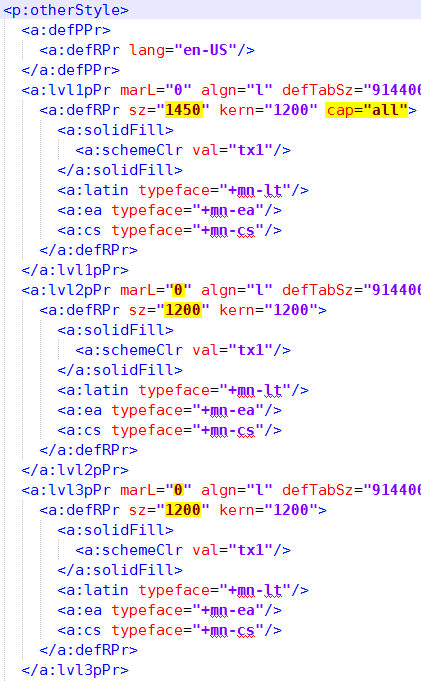

By default, PowerPoint always saves its Office themes as the last in the list. The way around this is to create a new, blank presentation, then create color and font themes before saving for the first time. If you save first, the default Office color and font themes will be saved into your template in last place. You can always ignore the last file in the themes folder. We’re only going to edit the first 3. When you open up Theme1.xml and expand it to readable form, the first part of the theme looks like this:

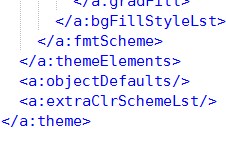

The editing were’ going to do occurs at the bottom of each theme, so let’s scroll down. The screen cap below shows the end of an unedited theme. The part we’re going to expand is the extraClrSchemeLst stub.

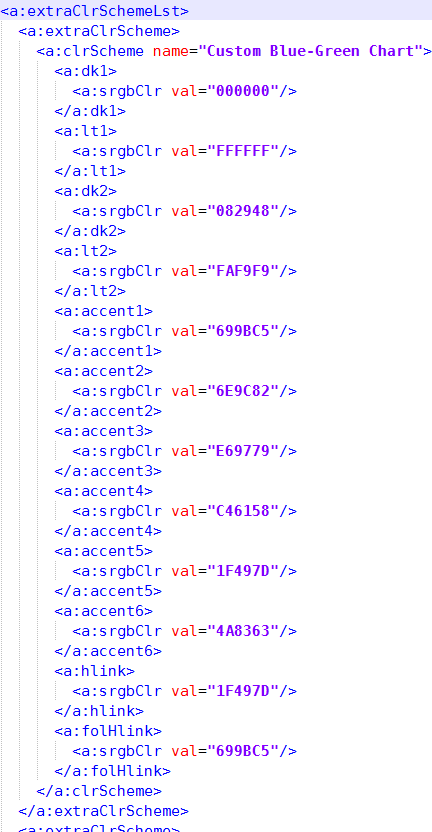

First we split <a:extraClrSchemeLst/> into opening and closing tags: <a:extraClrSchemeLst> and </a:extraClrSchemeLst>. Then we can insert color themes between them. When we’re editing the Custom theme that is applied to slides by default, we can color themes for the other themes 2 and 3. Here’s the first extra color theme: I just opened theme2.xml to get the values for this.

Then add the color scheme from theme3.xml and save. Theme1.xml is complete.

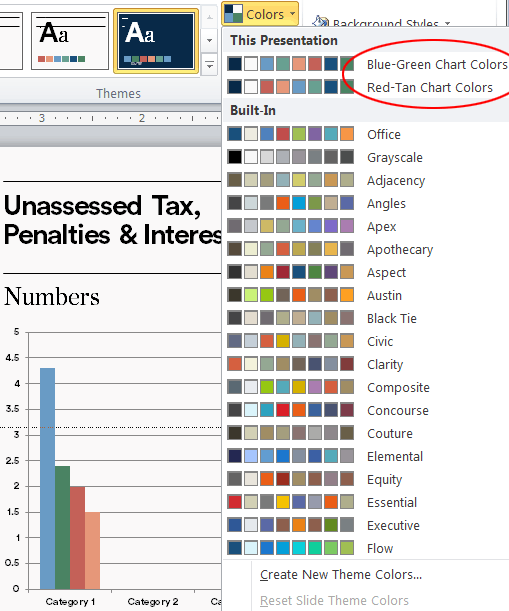

Now open theme2.xml and add extra color themes from theme1.xml and theme3.xml. Finally add the colors from theme1.xml and theme2.xml to theme3.xml. Phew! Now every theme contains every color theme. Zip all the xml files back into a presentation and let’s see how this improves the user experience in PowerPoint. After opening the file and moving to a chart that is based on the default master and theme, we can click on Design:Colors and the extra color themes show right at the top of the list:

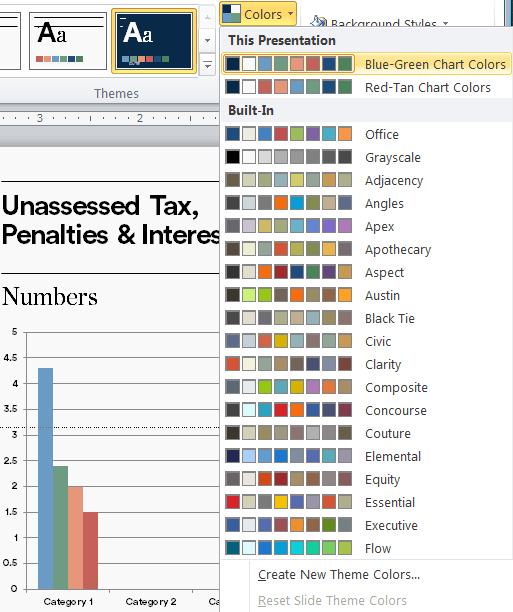

Selecting an alternate color theme instantly recolors the chart on the selected slide:

Thanks for reading. Next time I’ll discuss how to add even more custom colors when they won’t all fit into a color theme. If XML hacking isn’t your thing, we can do it for you. Contact me at production@brandwares.com.